Hong Kong Land Lease Reform, Part 1

7 October 2010

A few months back, in our article "Larvotto - do you know the boatyard?", we made a passing reference to the fact that, like many properties in the HKSAR, it stands on relatively short leasehold land - in Larvotto's case, 37 years remaining until what we call the "Second Handover" on 30-Jun-2047. We also mentioned in our article Conduit Controversy on 39 Conduit Road that the lease has 51 years remaining, until 19-Nov-2061.

We promised to return to the subject of HK's leaseholds in a future article, and this we now do. It is no exaggeration to say that the terms of sale of land leases are pivotal to the government's revenue and to the dominance of the property tycoons in the real estate market. Over the years since World War II, what started as a relatively balanced situation between ground rents and up-front premiums has morphed into a system of very low ground rents and massive up-front premiums for the right to develop or redevelop land. This has the following consequences:

- only a handful of large developers have big enough balance sheets to afford large-scale projects on their own, reducing competition;

- the Government receives lump-sum revenues in return for future land use, rather than recurrent ground rents which would smooth out revenues and allow it to match future expenditure with income;

- as a result, the Government piles up cash and then invests it in the markets, creating conflicts of interests;

- the Government earmarks the land premiums in the Capital Works Reserve Fund, and then feels obliged to spend it on infrastructure projects regardless of their economic value; and

- businesses and individuals have excessive amounts of capital tied up in properties, rather than paying less up-front and carrying obligations to pay future ground rents.

Current Government policy, but not law, is normally, in it sole discretion, to grant 50-year extensions of expiring leases without payment of premiums, but in return for an annual ground rent of just 3% of adjustable rateable value (the rent the property would fetch), leaving the other 97% for the leaseholder, a huge windfall. A future administration could and should change that policy, along with the high-premium low-rent policy on new land sales and lease conversions. For renewals, it would be unfair to shock the market with a change in policy near 2047, when many leases expire, but to change the policy now, with over 36 years to go, would not have a major impact on values.

We will advocate a solution to these problems in more detail in Part 2 of this article next week, but first, it is important to set out the historical context and to explain the various tenures of existing land leases in HK, which evolved from the beginning of the colonial era.

The beginning

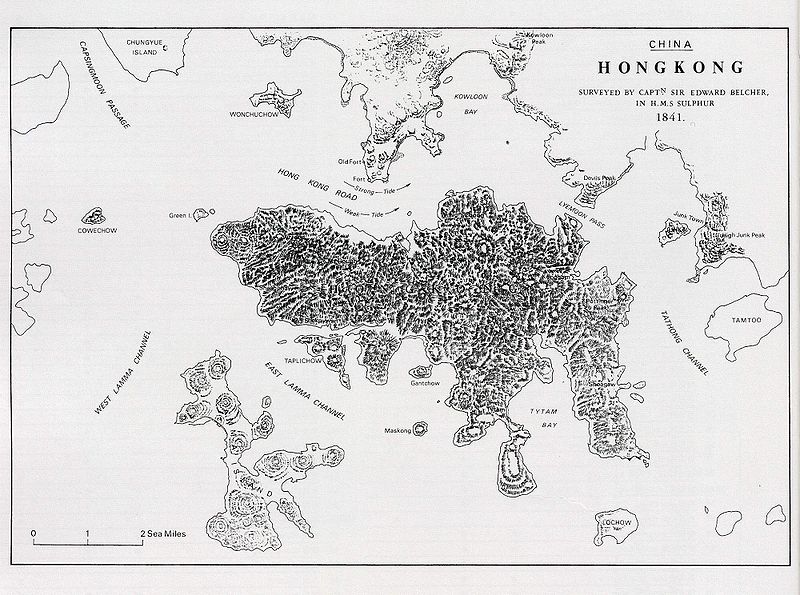

The British took possession of Hong Kong Island on 26-Jan-1841 (although Captain Edward Belcher of HMS Sulphur landed a day earlier), and Captain Charles Elliot, who was then in charge, had to organise a system for the allocation of land, although as you will see, it was flawed - he was a Navy man, not an economist. This was in the midst of a land grab by the opium traders such as Jardine Matheson, who had inspired the war in the first place. Waterfront land was particularly important, not for the views (as it is today) but for the ability to build wharves and godowns (warehouses) for shipping and the potential to expand it by private reclamation, as many early owners did. Captain Belcher's map of 1841 is below (click on it for a larger version):

On 1-May-1841, Elliot published a draft notice from Macau, with some blanks relating to the number and extent of allotments and period of sale, declaring that:

"Arrangements having been made for the permanent occupation of the Island of Hongkong it has become necessary to declare the principles and conditions upon which allotments of land will be made, pending her Majesty's further pleasure...

Each allotment to be put up at public auction at a certain upset rate of quit rent and to be disposed of to the highest bidder; but it is engaged upon the part of Her Majesty's Government, that persons taking land upon these terms shall have the privilege of purchasing in freehold (if that tenure shall hereafter be offered by Her Majesty's Government), or of continuing to hold upon the original quit rent, if that condition be better liked....

In order to accelerate the establishment, notice is hereby given that a sale of [BLANK] town allotments, having a water frontage of [BLANK] yards, and running back [BLANK] yards, will take place at Macao on the [BLANK] instant, by which time, it is hoped, plans, exhibiting the water front of the town, will be prepared.

Persons purchasing town lots will be entitled to purchase suburban or country lots of [BLANK] square acres each, and will be permitted, for the present, to choose their own sites, subject to the approval of the Government of the Island..."

The "quit rent" means the annual rent for exclusive use of the land, and the "upset rate" was the reserve price or minimum acceptable bid. So people were bidding based only on the amount of rent they would pay, even though the intent of the land was long-term building use. The flaw in this policy is that if market rents go down, then the leaseholder has a net liability and might even default or hand the land back, although that would be short-sighted if you had a long tenure and could expect future inflation of market rents to put you back in the black - but no tenure was specified. You will note that Elliot planned to throw in some "suburban" or non-waterfront land (later known as "Town Lots" and now as "Inland Lots"), presumably so that the merchants could build their mansions and shops.

On 7-Jun-1841, Captain Elliot filled in the blanks as follows:

"Notice is hereby given, that a sale of the annual quit rent of 100 lots of land having water frontage will take place at Hongkong, on Saturday, the 12th instant, as also of 100 town or suburban lots..."

Note that the venue had moved from Macau to HK. It turned out that they didn't have enough land for 100 seafront lots (later known as "Marine Lots") along the North side of the present Queen's Road, and they did not have time to mark out the suburban lots, so the sale was delayed two days, and restricted to Marine Lots with the following terms of sale on 14-Jun-1841:

- Upon a careful examination of the ground, it has been found impossible to put up the number of lots named in the Government Advertisement of the 7th instant, and only 50 lots, having a sea frontage of 100 feet each, can at present be offered for sale. These lots will all be on the seaward side of the road. Lots on the land side of it, and hill and suburban lots in general, will yet require some time to mark out.

- Each lot will have a sea frontage of 100 feet, nearly. The depth from the sea to the road will necessarily vary considerably. The actual extent of each lot as nearly as it has been possible to ascertain it will be declared on the ground. And parties will have the opportunity of observing the extent for themselves.

- The biddings are to be for annual rate of quit rent, and shall be made in pounds sterling, the dollar in all payments to be computed at the rate of 4s 4d. The upset price will be £10 for each lot, the biddings to advance by 10s..."

Some translation is needed: in British currency up to decimalisation in 1971, there were 20 shillings (s) in a pound and 12 pence (d) in a shilling. If you are wondering, the "d" is for denarius - a Roman coin worth 10 asses. So in decimal, the exchange rate the Captain refers to is 1 dollar to 21.67p, or about 4.62 dollars per pound. Incidentally, the "dollars" he refers to would be the Spanish/Mexican silver dollar which was the world's trade currency back then, and on which the US dollar was based.

All this was to some extent being made up by the Captain as he went along; keep in mind that telegraph cables did not reach HK until the 1870s. A New York Times article of 25-Jul-1871 records that the final splicing of the China Submarine Cable occurred on 11-Jun-1871, "placing Hong Kong in communication with Singapore and other parts of the telegraphic world as far as San Francisco". A Gazette notice of 10-Jul-1871 advises mariners what to do if their anchors pick up the cable. So prior to that, all communications between HK and London travelled by ship, leaving remote military men with a lot of discretion. The Suez Canal did not open until November 1869, so shipping times were longer too, unless you went "overland" between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean.

China and Britain were technically still at war. Captain Elliot had proposed the Convention of Chuanbi with Governor Qishan of Guangdong on 20-Jan-1841, which included the cession of HK Island, but also allowed the Chinese to continue levying duties. Neither the British Government nor Chinese Emperor ratified it, and both Elliot and Qishan were dismissed. Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, dismissing Elliot by letter of 21-Apr-1841, famously called HK "a barren island with hardly a house upon it."

So HK Island had been seized (six days after the Convention of Chuanbi), but it wasn't until 29-Aug-1842 (after the British attacked several more coastal cities) that the Treaty of Nanking (full text here) was signed aboard HMS Cornwallis, ceding Hong Kong Island to Britain "in perpetuity", without Chinese duties, and this was eventually ratified. So the initial HK land auction was held even before the colony legally existed. Elliot's replacement, and the British signatory to the treaty, was Henry Pottinger, who became the first Governor. HK Island and its dependencies formally became the "Colony of Hongkong" by Royal charter dated 5-Apr-1843. The ratified treaties were exchanged in HK on 26-Jun-1843. This became the base date for the first land leases. On 21-Aug-1843 the HK Government announced extracts from instructions from Lord Stanley, Secretary of State for the Colonies, basically saying that there would be no automatic recognition of the previous allotments, but to avoid chaos on occupied sites, claims would be entertained:

"Sir Henry Pottinger is to abstain from alienating any of the land on the island, either in perpetuity or for any time of greater length than be necessary to induce and enable the tenants to erect substantial buildings,...

But with the general prohibition against the alienation of Crown Lands, and with the general refusal to sanction any such grants as may have already been made, Lord Stanley would connect a promise that immediately on the establishment of a regular Government in the place an enquiry should be instituted, by some competent and impartial authority, into the equitable claims of all Holders of Land..."

Introduction of 75-year tenures

In the hurry to stake out land and make a start on buildings, no lease duration had been decided, and even the possibility of freehold had been left dangling "if that tenure shall hereafter be offered". It wasn't, with the exception of St John's Cathedral, but only so long as it is a church. The Government committee ordered by Lord Stanley reported on 4-Jan-1844, recommending that all the pre-colony Marine Lots should be confirmed for 75 years, except those which had been abandoned or forfeited. On 28-Feb-1844, the Land Registration Ordinance was passed, requiring the registration of all leases and dealings.

Extension to 999-year tenures

Much of the above history and more can be found in the Report from the Hongkong Land Commission of 1886-87. Apparently with the economy not going so well, the landowners soon started complaining about the tenure and the "high Crown Rents". Governors Sir John Davis and later Sir George Bonham made representations to London, pointing to the fact that Singapore had 999 year leases. Earl Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, gave approval, and on 3-Mar-1849 it was announced that all Crown Leases previously granted for 75 years could, on application, be extended by 924 years, making them 999 year leases. Of course, most leaseholders applied.

Introduction of lease premiums

Further discussion continued, and in despatch No. 222 from Earl Grey to Governor Bonham of 2-Jan-1851, he concluded that in future, Crown Land should be:

"offered for lease at a moderate rent to be determined by the Crown Surveyor and that the competition should be in the amount to be paid down as a premium for the lease at the rent so reserved by parties desiring to obtain it".

That is basically the way land is still leased in HK, at a premium plus rent, rather than just rent, although the balance between these has radically changed as we will discuss below. For the rest of the 19th century and at least up to the Japanese invasion in 1941, typical annual rents for leases sold by auction were several per cent of the minimum sale price. For example, if the fixed rent was 5% of the minimum sale price, taking a long-term discount rate of 5%, then this basically implied that half of the net present value would be received as future crown rents, and the other half as the up-front premium.

The crown rents on new leases were determined by a broad classification system, later known as "zone crown rents", in terms of dollars per acre of land. This scale was revised from time to time. Most of the thought went into setting the reserve price for the auction, which would depend on finer details such as the position of the lot, elevation and accessibility. We've analysed all the advertised land sales in Gazettes between 1871 and 1900, and it is clear that sometimes the auctions failed to find buyers at the reserve price, as the allocated lot numbers were reused in another sale shortly thereafter. So it is a fair inference that the reserve prices were not generously low for the time.

Kowloon and Stonecutter's Island

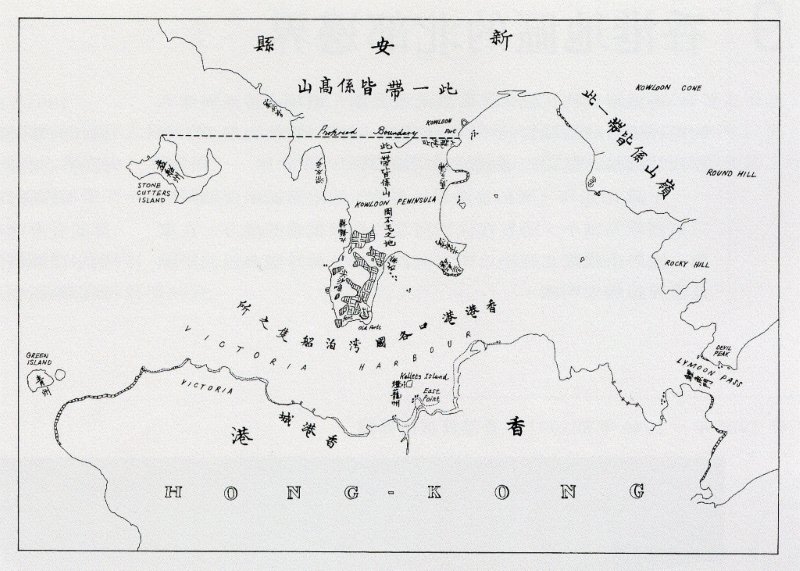

Following the first part of the second opium war, there was the Treaty of Tianjin (then "Tien-tsin") signed on 28-Jun-1858 and amended and ratified as the Convention of Peking on 24-Oct-1860 at the end of the war. Between these two events, Harry Smith Parkes, one of the "Allied Commissioners for the Government of the City of Canton", which was under Anglo-French occupation from 1858-1861, had signed a lease dated 20-Mar-1860 with "Lau Tsung Kwang, Governor General of the two Kwang" (Kwang-tung and Kwang-se, now Guangdong and Guangxi provinces) for "certain portions of the Township of Kowloong". Four days later, on 24-Mar-1860, the Hongkong Gazette included a proclamation of the lease, for "that part of Kowloon peninsula lying South of a line drawn from a point near to but South of the Kowloon Fort to the Northern-most point of Stone-cutter's Island, together with that Island".

This lease was replaced by Article VI of the Convention of Peking, which ceded the same area to Britain in perpetuity. The map below is from the Convention (click on it for a larger version).

By a proclamation dated 28-Mar-1861, the laws of HK were applied to Kowloon.

The stated reason for the cession of Kowloon in the Convention of Peking was "the maintenance of law and order in and about the harbour of Hongkong" - in other words, a buffer zone. Initially, the British did not do much with it. On 18-Aug-1873, the Government announced that it would grant 14-year leases for garden purposes, terminable after 7 years at the option of the lessee. The earliest such land auction we can find is Garden Lot No. 2, an acre of land leased in 1873 for $20. Sales of sites for buildings got underway by 1876, when 75-year leases were offered in Yaumatei, so those started to expire in 1951.

By the Land Commission's reference date of 25-Dec-1886, in Kowloon there were 113 Inland Lots, 15 Marine (waterfront) Lots, 9 Farm Lots and 68 Garden Lots. The early Kowloon Marine Lots are the only lots in Kowloon which have 999 year leases - the last such auction we can find was KML 3 and KML 6 on 21-May-1889. After that, they were 75-year leases until the change of policy in 1899 (see below) when renewable leases of 75+75 years were introduced.

Rural Building Lots

Rural Buildings Lots (RBLs) hold residential property, mostly low-rise apartments and houses on The Peak and (more recently) the South side of HK Island. The 1887 Land Commission report mentioned that at 25-Dec-1886, there were just 43 RBLs, each with a 75 year lease. Those original terms have of course expired. The first such 75-year lot, RBL 1, was auctioned on 30-Sep-1878, so that expired in 1953, and the last 75-year RBL, Number 97, was auction on 8-May-1899, so it would have expired in 1974. After 1899, RBLs were on renewable 75+75 year terms (see below), so they start expiring in 2049.

Searching through listed company documents, the earliest current RBLs in our survey are RBLs 522, 639 and 661, which are the land under Mountain Court, 11-13 Plantation Road, The Peak, each with a 150 year lease from 10-Dec-1877, so that term expires in 2027, without a right of renewal. On that day in 1877, there was an auction of Farm Lots at that location, so the leases were probably subsequently exchanged (upon payment of a conversion premium) and extended as RBLs.

The New Territories

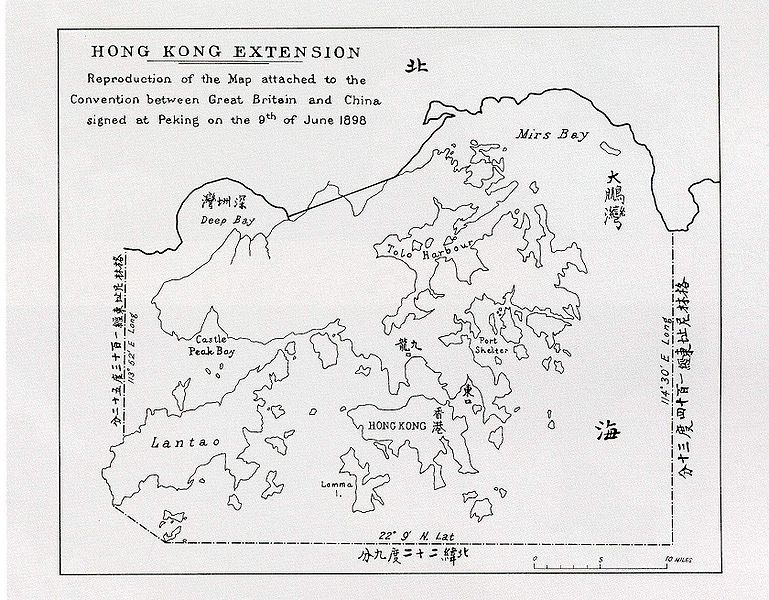

The Second Convention of Peking was signed on 9-Jun-1898 in Peking (Beijing), leasing the New Territories (NT) for 99 years to 30-Jun-1997. Under royal order and the Governor's proclamation, the laws of HK were applied to the NT with effect from 17-Apr-1899.

NT land which was in private ownership when the lease began in 1898 was recorded in "Block Crown Leases" (BCLs), with one BCL for each of 477 "Demarcation Districts" (DDs). Annexed to each BCL was a list of lots in the DD, with the crown rent, user and owner. These were known as "Old Schedule Lots". All of these leases were for 75 years renewable for "24 years less three days", so the first expiry was on 30-Jun-1973.

There were also "New Grant Lots" (NGLs) - leases granted in the NT after the start of the NT lease. Until Oct-1959, these were also granted for the same 75+24 year period starting 1-Jul-1898. From Oct-1959, this became simply 99 years from 1-Jul-1898 "less the last three days". We don't know what the Government was planning to do for the last three days before the head lease expired!

So for all the Block Crown Leases and any New Grant Lots granted before Oct-1959, the renewal date was 1-Jul-1973.

No more 999 year leases, introducing 75+75 renewable leases

On 23-May-1898, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, gave instructions that, without further reference to him, no further 999 year leases were to be sold. He considered that the Crown was being deprived of any benefit of the increase in value of land with the passage of time, and wanted to reduce future leases to 75 years. or "at the outside" 99 years. From contemporary Gazettes, we can see that auctions were held on a 75-year basis from 20-Jun-1898 to 24-Jul-1899, with just two unusual 99-year leases.

The reduction prompted protests from the Chamber of Commerce and (according to a legislator in a debate on 10-May-1972), the Colonial Secretary wrote to the Chamber with a compromise:

"Terms will be embodied in future leases that leases will be renewed...upon such an advance in Crown rent as is justified by the then value of the land and without fine for a further period of 75 or 99 years, and that in the event of the land being resumed by the Government for public purposes compensation will be given."

Translating to modern English, by "advance" he meant "increase" and by "fine" he meant "premium". The question of how this rent would be assessed was left unaddressed. As a result, the Government introduced the "75+75" year leases, with a single right of renewal for a 75 year period, "at a Crown Rent to be fixed by the Surveyor of Her Majesty". From contemporary Gazettes, we note that the first 75+75 land auction was held on 31-Jul-1899, for Inland Lot 1558 on Queen's Road East.

From Gazettes, we note that the last 999-year lease sold at auction was Inland Lot 1485 on Peak Road, on 31-May-1898. The last 999 year lease we can find in other records is Marine Lot 287, currently part of the site for Chater House, 9-25 Chater Road, Central, which runs from 24-Dec-1901. One possible exception is the USA Consulate on Garden Road, which is rumoured to have been granted a 999-year lease, although we have been unable to verify this.

Update, 6-Aug-2018: we have now verified this, see our article: Revealed: the USA has the longest land lease in China (6-Aug-2018).

Regrants

As noted above, 75-year Kowloon leases were auctioned from 1876 and 75-year RBLs were auctioned from 1878, so these started to expire in 1951 and 1953 respectively, and thereafter in increasing numbers, without any legal right to a new lease. As early as 16-May-1946, in the first regular session of the Legislative Council after World War II, Governor Mark Young said (p22):

"I have already had under consideration the question of the renewal of Crown Leases which are due to expire in the near future. The committee has rightly asked that a speedy decision 'may be reached on this important matter and I hope that a public announcement will be made in the very near future."

A month later, on 16-Jun-1946, the Government announced its policy in regard to the renewal of 75-year leases. Unless the Government needed the land for public purposes, it offered new leases, or "regrants", using the contemporary zone crown rental and assessing the full and fair market value of the land lease (excluding buildings). In a concession, for applications in the first year, the premium was reduced to the extent of one half of the cost of rebuilding premises which were damaged during the war, as many were.

In offering regrants after the war, due to the shortage of housing, the Government required an increase in the extent of developments on some of the RBLs, prompting complaints from Jardine Taipan David F Landale in LegCo on 3-Jul-1947 (p4 onwards) and 10-Jul-1947 (p7 onwards) that the policy was oppressive, due to construction costs! How times have changed, since for many decades developers have strained every sinew to maximise the size of the developments on their sites within legal limits.

In a concession introduced in 1960, the Government allowed the premium for regrants to be payable in up to 21 annual instalments with interest at 10% p.a.. In a later concession, it allowed holders to apply for a lease which contained a restriction on redevelopment by limiting the size of building to whatever was already on the lot, thereby reducing the value of the land and the premium payable.

In order to provide some certainty, it also allowed leaseholders to apply for regrants up to 20 years before expiry, so that the holder would not be left with a dwindling lease which would be less saleable due to the unknown cost of renewal, and might disincentivise building maintenance.

To deal with multi-owner lots, such as the land under many apartment blocks, where owners have "undivided shares" in the lot, the Crown Rent and Premium (Apportionment) Ordinance was passed on 6-May-1970, so that each owner was only liable for his share of the rent and premium rather than being jointly liable with all the other owners. At the same time, the Crown Rights (Re-entry and Vesting Remedies) Ordinance was passed, so that when a regrant was offered, the shares belonging to owners who did not participate would be transferred to the Government and eventually resold.

The renewals begin early

Although newly granted 75+75 leases, from 1899 onwards, would not start hitting their renewal dates until 1974, there were some other leases which hit the renewal date sooner. That's because some non-renewable 75-year leases such as RBLs and some old Kowloon leases had been granted before 1899 but modified after 1899 (for example, to subdivide the lot or change the type of lot). At least in some cases, when they were modified, they were offered either the previous lease term, or (for a modest premium) an additional right of renewal.

As we mentioned earlier, the right of renewal was without payment of premium, but the question of how the ground rent should be calculated was left dangling. An important test case of how the renewal clause in the lease should be interpreted, and hence what the new rent should be, was Chang Lan Sheng v Attorney General, which went all the way to the UK Privy Council, the highest court. The standard wording in the original lease for the annual amount of rent payable on the renewed lease was:

"such Rent as shall be fairly and impartially fixed...as the fair and reasonable rental value of the ground at the date of such renewal"

The Court of Appeal judgment of 25-Sep-1968 (which was upheld by the privy council) explains the case. The original lease of Kowloon Inland Lot 539, was for 75 years from 24-Jun-1888. It was subsequently split, and then in 1936, the lessees of the various sections agreed with Government to each obtain new leases. Some chose the original lease term, and other chose to buy a right of renewal, exercisable when the original lease expired in 1963. The holder of section Q chose a renewable lease, which was registered as KIL 3793. In 1963, the subsequent holder exercised the right of renewal. He had redeveloped twice, from a 2-storey villa to a 5-storey building in 1952 and then a 10-storey building completed in 1964. Looking on Google street view today, we see Houng Sun Mansion, at 45-47 Carnarvon Road, still the 1964 version. The judgment notes that the building cost $830,000.

The Government assessed the value of the land (what a willing buyer would pay in an auction) at $1,234,875, and using a discount rate of 5%, converted that into an annual rental value of $60,764, including the nominal "zone crown rent" that an auction buyer would have to pay anyway, and allowing for half-yearly payment in advance. Readers can think of this "decapitalisation" as a 75-year repayment mortgage with a 5% interest rate. By the 1960s, zone crown rents bore no resemblance to the economic rental value of the land, they were just there so that the lease involved some nominal payment, with virtually all the value of newly sold land being in the up-front premium.

The Court of Appeal ruled that the Government had fixed the rental value in accordance with the renewal clause in the lease.

In passing, one of the appeal judges in Chan Lan Sheng noted in 1968, when comparing the renewal in this case with regrants of non-renewable leases nearby:

"what is also very obvious from the plaintiff's schedule is that during the last 10 years lessees have been getting most favourable terms on certain regrants....

What appears to emerge from the whole of the evidence is that about the beginning of 1963, the Hong Kong Government realised that the public (as represented by Government) was not getting its fair share of rising property values...it was decided (probably for the first time in the history of Hong Kong) that in future land values would be worked out strictly in accordance with generally accepted land valuation principles. Naturally, Crown lessees, who had been making fortunes out of land for years, did not like it."

Renewal in the New Territories, 1973

Meanwhile, another issue was looming. According to the lease conditions for BCLs and NGLs, the leases were for 75 years renewable for 24 years, using the same language as the 75+75 leases discussed above. In early 1967, with the background of growing social tensions from the Cultural Revolution across the border and no doubt with pressure from indigenous villagers, the Executive Council decided, with the approval of the Secretary of State, that although this clause allowed a large increase in rent, it would not be exercised. Eventually the New Territories (Renewable Crown Leases) Ordinance (NTRCLO) was enacted on 9-May-1969, deeming all NT leases registered in district office land registries (except for 82 special lots) to be renewed at the same fixed rent as before. Explanation can be found in the LegCo Hansard of 9-Apr-1969 (PDF p11).

Renewal of 75+75 leases

The situation in HK Island and old Kowloon, however, was different. There was no good reason why someone who had purchased a lease with a right of renewal should not expect to have to pay up a fair rent to renew it, because that is what the lease said, and it had been tested in the highest court. The right of renewal did not mean the right of a gift.

On 10-May-1972, Oswald Cheung, a barrister and legislator, raised objections (p25 onwards) in LegCo to "the present levels of re-assessed Crown rents on renewable leases" and asked for them to be "substantially less". He rather disingenuously argued that "fair and reasonable" should not mean full market rent (or rack rent) but "somewhere about half or 40% of the rack rent". Wilfred Wong Sien Bing chimed in with "for Government to charge what the market can bear is wrong in principle and practice".

Chung Sze Yuen argued that where premises have been mortgaged to banks, the borrowers may have trouble making payments if they have to pay higher crown rent - but that assumes banks were reckless enough to lend against a lease reaching its renewal date. He was speaking in the aftermath of the bank runs of 1965, invoking fears of a repeat. Industrialist Ann Tse Kai complained that the revised Crown rents range from 0.8% to 3.9% of the turnover of factories, averaging 2.4%.

In response, Financial Secretary Philip Haddon-Cave claimed that the low assumed rate of interest (5%, versus borrowing rates over 10%) used in deriving renewal rents from capital values was a concession itself, resulting in the Government getting only about half of fair value. He also said that owners have been given the choice of renewing early and paying a lump sum, or paying over the term of the lease (75 years), or renewing on the basis of the existing development and paying a rent of about 30% of actual income from the property, or often less than that, by restricting the lease to redevelopment of the existing size of building. All of this was apparently set out in a "Consolidated Statement" in 1969, and was more generous than the terms of regrants noted above. He said:

"The fact is, however, that land owners generally form a comparatively wealthy segment of the community and have, by and large, done very well in Hong Kong in recent years. It is this segment of the community, which includes the large property companies, which stands to gain most if the present policy on renewal is changed in the way proposed by honourable Members. And it is the public interest, the wider interest of the community as a whole, which would be prejudiced by such a change."

You've got to hand it to Mr Haddon-Cave - he told it the way it was, and still is today. The Financial Secretary continued:

"Further concessions to this group of landowners would inevitably lead to demands for similar concessions from other categories of landowners - and the whole economic basis of our carefully thought out land policy would be seriously undermined..."

His robust defence of economic principles did not last long though. Two weeks later, on 24-May-1972, the Government announced (p15 onwards) some concessions, saying it would now use a 4% interest rate to decapitalise the premiums, and also for those who renewed in the 5 years up to 30-Jun-1973, they would phase in the rent payments, starting at 50% of the contractual rate and rising in 10% steps for the first 5 years of the new lease, but not backdated.

On 28-Mar-1973, the Government tabled (p11 onwards) the Crown Leases Bill 1973, which proposed to automatically renew the approximately 5,000 renewable lots in the NT (mostly in New Kowloon, i.e. north of Boundary Street) that were expiring on 30-Jun-1973 but were not covered by the NTRCLO. The terms were as announced on 24-May-1972. The Bill would also apply to 75+75 or the rare 99+99 renewable leases (on HK Island and old Kowloon) where the first term expired after 30-Jun-1973, and to a number of leases listed in a schedule for which the first term had expired in 1972 (plus 2 in 1959 and 3 in 1968 - we don't know why). In a further concession, the rental value of new leases expiring on or after 30-Jun-1973 would be the lower of the value of the ground on the expiration date and the value one year before expiry.

What followed was a rebellion by the non-government or "Unofficial" members of LegCo (keep in mind, they were all appointed by Government) who represented the powerful business interests of HK. The Bill came up for debate on 25-Apr-1973 (p22 onwards) and several members, including Woo Pak Chuen, Szeto Wai, Wilfred Wong Sien Bing and James Wu Man Hon spoke against it. In the face of this onslaught, Colonial Secretary Sir Hugh Norman-Walker sought an adjournment.

Then, on 20-Jun-1973, with 10 days to go before the NT leases were to expire, the Government caved in and announced, through the acting Attorney-General, that the renewal rents would be 3% of rateable at the date of renewal, fixed throughout the lease period. Rateable value is basically an estimate of the annual rent achievable for the property (including the building). It was probably the biggest windfall the developers and landlords ever had. The result was the Crown Leases Ordinance, which applies to any lease which has a right of renewal built in. Apart from conversions of pre-1899 leases, all of these renewable leases were granted between 1899 and 1985, so they will be coming up for renewal until 2060 in the case of 75+75, or 2084 in the case of 99+99 year leases (of which there are very few). Because the rents are fixed upon renewal, they decline in real terms due to inflation over the 75 or 95 year lease.

Leases after the Joint Declaration

On 19-Dec-1984, the UK and the PRC signed the "Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong" (JD). After ratification, this came into effect on 27-May-1985. The JD had an Annex on Land Leases, stating that from the effective date of the JD until 30-Jun-1997, leases could be granted for terms expiring not later than 30-Jun-2047, at nominal rental until 30-Jun-1997 and thereafter at 3% of the rateable value of the property adjusted for any changes in rateable value from time to time. This also applied to leases expiring before 30-Jun-1997 without a right of renewal. The rent was eventually enshrined in Article 121 of the Basic Law.

In practice, leases during the pre-handover period were granted for terms expiring on 30-Jun-2047, so they started with 62 years and diminished to 50 years by the time of the handover. An interesting example is provided by Pacific Place; part of the site (One Pacific Place and the Marriott Hotel) is on a pre-JD lease of 75+75 years from 18-Apr-1985 (less than 6 weeks before the JD) to 2135, while the rest is on a lease from 27-May-1986 to 30-Jun-2047.

Since the handover, new leases have been routinely granted for 50 years without a right of renewal, with ground rent at 3% of rateable value adjusted in line with rateable values. The only exception we are aware of is Hong Kong Disneyland, which has a right of renewal for a second 50-year period. That's the magic of Disney, where nothing is ever as it seems.

Renewals of leases expiring after 1997

That still left the question of what would happen to leases granted before the JD but expiring after the handover, if they did not have a contractual right of renewal. So this was dealt with by Article 123 of the Basic Law which says:

"Where leases of land without a right of renewal expire after the establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, they shall be dealt with in accordance with laws and policies formulated by the Region on its own."

On 15-Jul-1997, the HKSAR Government announced its current land policy for lease renewals. It said:

"Non-renewable leases will, upon expiry and at the Government's sole discretion, be extended for a term of 50 years without payment of an additional premium. However, an annual Government rent of three per cent of the rateable value will be charged from the date of extension to be adjusted in step with changes in the rateable value."

This is a policy, not a law, and it is open to future Chief Executives to change it. It is also open to future Chief Executives to propose amendments to local legislation, including the Government Leases Ordinance passed in 1973, which governs the terms of renewal of renewable leases. No Chief Executive can tie the hands of his or her successors, and there is no legitimate expectation that policies will not be changed in future if it is not unreasonable and is in the public interest to do so. In Part 2 of this article, we will explain how the policy could change to establish a stable recurrent rental income stream from land sales, land-use conversions and lease renewals, at the same time as lowering the barriers to entry for development and lowering the capital required for property ownership.

© Webb-site.com, 2010

Topics in this story

Sign up for our free newsletter

Recommend Webb-site to a friend

Copyright & disclaimer, Privacy policy