Justice is blind, except for haircuts

1 May 2018

Perhaps it should surprise you that three men who dress up in wigs and gowns (in their day jobs) believe in "conventional standards of appearance", but yesterday's ruling from the Court of Appeal has to be seen to be believed in the 21st century. In Leung Kwok Hung v Commissioner of Correctional Services, the Court of Appeal has overturned the judgment of Justice Thomas Au Hing Cheung in the Court of First Instance (CFI), and ruled that former legislator "Long Hair" Leung Kwok Hung did not face gender discrimination when, as a male convicted prisoner, his hair was cut short against his wishes, while female prisoners face no such requirement.

The requirements in HK

The HK requirements are set out in the "Standing Orders" issued by the Commissioner under Rule 77(4) of the Prison Rules. We have been unable to find the Standing Orders on the Commissioner's web site or anywhere else online, so we can only tell you the order quoted in the judgment. Standing Order 41-05, titled "Hair of prisoner", states:

These archaic rules have a clear ring of inconsistency about them. On the one hand, the "purpose" of the rule for men is said to be for "health and cleanliness", but on the other, no such need is identified for women. If there were such a need, then it would surely apply to both. Head lice have never expressed a preference for men.

We also note that the Order only applies to male "convicted" prisoners, not to prisoners who are remanded in custody pending or during trials. For those awaiting trial, Section 199 of the Prison Rules states:

"The hair of every prisoner awaiting trial may be cut but not in such a manner as may alter his appearance."

For those who are actually in trial (not awaiting it), the same rule presumably applies.

The requirements in UK

Given that HK prison rules undoubtedly descended from the UK, it is worth looking at the UK requirements and how they have changed. In the now-repealed Prison Rules 1964, section 26 titled "Hygiene" included a weekly bathing requirement and stated:

(2) Every prisoner shall be required ...in the case of a man not excused or excepted by the governor or medical officer, to shave or be shaved daily, and to have his hair cut as may be necessary for neatness: Provided that an unconvicted prisoner shall not be required to have his hair cut or any beard or moustache usually worn by him shaved off except where the medical officer directs this to be done for the sake of health or cleanliness.

(3) A woman prisoner's hair shall not be cut without her consent except where the medical officer certifies in writing that this is necessary for the sake of health or cleanliness."

However, by 1999, the Prison Rules had been amended to remove differences in the treatment of genders, giving men the same treatment as women. Section 28(3) of the Prison Rules 1999 simply states:

(3) A prisoner’s hair shall not be cut without his consent.

The reason for this reform is stated on page 66 of the Prison Reform Trust's Prison Rules: A Working Guide, which quotes a "Circular Instruction", CI 56 of 1989:

"it is thought inappropriate to maintain the distinction between provisions for male and female prisoners"

We could not find the original CI 56/1989 online, probably because it was issued 29 years ago, before the web existed, which is a reminder of how far behind HK is. Perhaps in the UK in 1989 it was "thought inappropriate" to have different rules for men and women because of the Sex Discrimination Act, passed in 1975 (20 years before HK passed the SDO). Unfortunately, Mr Leung's counsel do not appear to have raised the UK history of prison rules in their arguments.

Incidentally, the UK is far more transparent, with all the current Prison Service Instructions and Prison Service Orders online, despite HK's claims to be a Smart City.

The Court of First Instance judgment

Section 5 of the Sex Discrimination Ordinance (SDO) outlaws discrimination on the grounds of gender (it is worded for women, but applies equally to men due to Section 6). A person suffers discrimination if he/she is treated "less favourably" (not just differently) on the ground of his/her gender. Mr Leung was clearly treated less favourably than a woman, by being denied the choice of whether to keep his hair long. Under this test of direct discrimination, there is no test of justification or purpose for the discrimination.

In the CFI, the Commissioner sought to revise the stated purpose of "health and cleanliness" of men (but not women) by claiming that the objective was "to provide a secure, safe, humane, decent and healthy environment for people in custody by maintaining prison security and custodial discipline". The perceived risks included vulnerability of long-haired prisoners in an attack, the risk of concealing prohibited items in their hair, the risk of violence associated with triad or gang affiliation and the risk of prisoners committing self-harm or suicide with their hair, all of which the Commissioner considered "partly backed by some statistics" to be more likely in men than women.

Justice Au was having none of this. He wrote: "The Commissioner's purported reasons are all based on stereotyped or generalised assumptions referable to the purported risks associated with male prisoners as a gender as a whole" and "as a matter of law, a purported ground based on stereotyped or generalised assumptions referable to a particular sex (even if supported by statistics) is similarly caught by section 5 of the SDO as a non-permissible ground of direct discrimination." That must be right, of course. If a football stadium could prohibit men but not women from bringing in knives, because men are statistically more likely to use them, that would be discrimination against men. If an army could exclude all women because the average woman is physically weaker than the average man, that would be discrimination against women.

Put simply, if the goal was to eliminate risks associated with long hair, then the rule should apply to women too, because even if women are at lower risk, they are not immune. Girls fight too.

On a separate ground of judicial review, Mr Leung claimed that the rule infringed the rights of male prisoners under Article 25 of the Basic Law which provides that "All Hong Kong residents shall be equal before the law" - or in this case, all prisoners. A restriction or violation of a constitutional right must satisfy a 3-pronged "proportionality test", that is, it must have a legitimate aim, must be rationally connected to that aim, and be no more than is necessary to accomplish that aim. As Justice Au put it:

"It is quite obvious that the Commissioner could also achieve the same purposes in a non-discriminatory way by applying the same hair cut requirement to both male and female prisoners."

So although Mr Leung had succeeded on his first ground, Justice Au ruled that he would also have succeeded on this second ground.

You might think the outcome was so obvious that this was the end of it. The Government could have just thanked Mr Leung for drawing attention to an outdated and discriminatory rule that had long since been replaced in the UK to prevent discrimination. The Government could have said that the failure to amend the rule after the SDO was passed was an "administrative oversight" and copied the modernised UK prison rule allowing all prisoners to have long hair if they wish, or amended the rule to require women to cut their hair short too. But in HK, the Government will never admit discrimination until all legal avenues are exhausted. We can't help wondering whether the determination of the Government to uphold this obsolete rule is based partly on the identity of the claimant, who as a long-time political opponent must not be allowed to score a victory, even if it is for common sense.

The Court of Appeal judgment

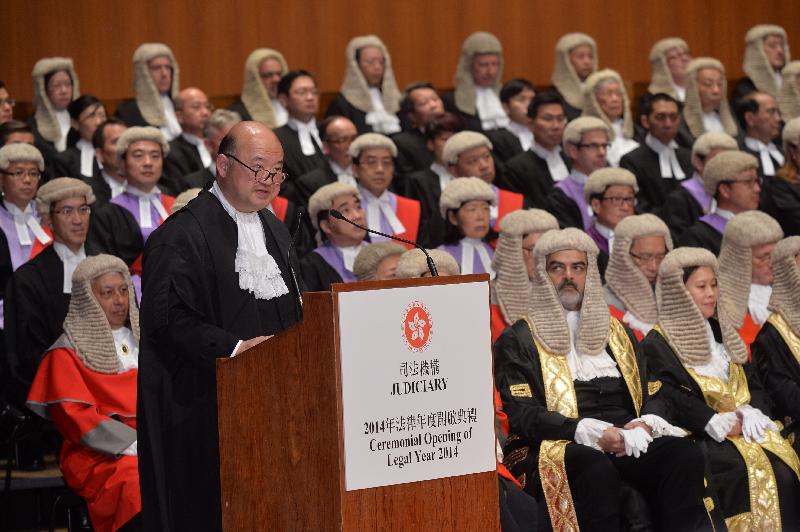

In the unanimous judgment overturning the first instance judgment, there is almost no reference to the purported health and safety reasons advanced by the Commissioner in the CFI and rejected by Justice Au. Instead, there is a focus on a completely different line of reasoning involving discipline, conformity and societal norms. There are separate analyses by two of the three judges, Chief Judge Andrew Cheung Kui Nung and Vice President Johnson Lam Man Hon, but with a common theme. Justice Jeremy Poon Shiu Chor simply concurs. Incidentally, subject to LegCo approval, Justice Cheung will rise to the Court of Final Appeal in October.

In the judgment, Justice Cheung goes first. He states that according to the "unchallenged evidence" (none of which is referred to in the CFI judgment) the haircut requirements are:

"based on and by reference to the conventional hairstyles of male and female persons in Hong Kong society. In other words, a full and complete description of the treatment that one is concerned with in the present case is that an inmate, whether male or female, is required to wear a hairstyle that conforms to the conventional hairstyle of people in Hong Kong of his or her own sex. As, according to the evidence, the conventional hairstyle of male persons in Hong Kong is a short hairstyle, male inmates are therefore required to wear a similar short hairstyle. On the other hand, as the conventional hairstyle of Hong Kong women is that it may either be long or short (putting the matter in a simplified way), female inmates are therefore allowed under the female haircut requirement to keep their own hairstyles. Female inmates are not required to have their hair cut short only because according to the conventional hairstyle for women in Hong Kong as it is, it may either be long or short as women hairstyles do vary and a predominant hairstyle with a particular hair length cannot be identified."

By this tortuous reasoning, Justice Cheung says that Mr Leung is not discriminated against (treated less favourably), because societal norms for men and women are different. Most men have short hair, therefore Mr Leung must have short hair, whereas women have a range of hair length and therefore female prisoners are "required" to do what they like. This to us seems to be exactly the kind of "stereotyped or generalised assumption" that Justice Au said was not permitted as a justification for direct discrimination.

The statement also seeks to portray the free choice of female prisoners on their hair length as a "requirement" to conform to a "conventional hairstyle" that cannot be identified. It is rather like claiming that a conventional standard car colour in Hong Kong is "any colour you like". It strains credulity to define free choice as a "conventional standard". A requirement that confers a choice of all possible outcomes is no requirement at all. Imagine the futility of passing a law which says that "your car must be any colour(s) you like". The statement overlooks the fact that the norm in society (outside prisons) is "free choice" for hair length by both men and women, even if most men choose to keep their hair short (and to shave their face).

There is more of this nonsense in Justice Lam's section, but first, Justice Cheung seeks to redefine Mr Leung's complaint for him, stating that "when examined analytically" and "when translated into legal terms" his complaint is not of direct discrimination, but of indirect discrimination, for which a justification can be allowed. But Justice Cheung's reasoning depends on his rejection of the claim of "direct discrimination" due to his "conventional standard" reasoning. So if that was wrong, then Mr Leung was indeed claiming direct discrimination. The reasoning seems to be "because I say you were wrong, you must have been claiming something lesser".

However, in Justice Cheung's own words, indirect discrimination is the result of applying:

"an apparently gender‑neutral criterion which, by nature or in practice, favours a man as compared to a woman (or vice versa)".

This is covered by Section 5(1)(b) of the SDO. To take Justice Cheung's example, a requirement that job applicants must be over 6 feet tall favours men over women because a greater percentage of men than women exceed that height, but it is allowable if it is necessary for that job. That's not the case with the Standing Order on haircuts. The criterion for whether a person has free choice over hair length is clearly based on gender, it is not "apparently gender-neutral" despite the court's strenuous efforts to redefine it as a requirement that the hairstyle "conforms to the conventional hairstyle of people in Hong Kong of his or her own sex" - because again, that interpretation refers to the gender of the prisoner with the words "his or her own sex".

Justice Lam then picks up the baton, and continues with a line of reasoning that the narrow issue of haircuts should be seen as part of a broader package of discipline:

"For example, in respect of the restrictions on keeping (and using) make-ups, female inmates are allowed to keep (and use) specified lipsticks but not allowed to keep other forms of cosmetic makeup. Obviously there is a difference between male and female inmates in that regard. However, because of the conventional standard for appearance in our society, such difference cannot be regarded as less favourable treatment for male inmates. Further, given the prevalence of use of makeup for women as compared with men in our society, the restriction is more relevant for female inmates. However, taking other restrictions on appearance into account, on the whole it cannot be said that a more stringent set of restrictions are imposed on female inmates. This highlights the need to examine all the restrictions as a package overall."

If anything, this rather points to further discrimination against men if they are not permitted "to keep (and use) specified lipsticks" as a few men like to do. Presumably all prisoners (not just women) are "not allowed to keep other forms of cosmetic makeup", so at least that part is fair. Justice Lam misses the point that women are not required to cut their hair but men are. There is no requirement on women prisoners to keep or use lipsticks - it is a right, not an obligation.

Justice Lam then returns to Justice Cheung's line of reasoning and argues:

"As explained above, the policy of the Commissioner was set by reference to the conventional standards of appearance for men and women in our society...it is an objective fact that these conventional standards exist and they are observed by most people in our society"

That is a circular argument. Something cannot be a "conventional standard" unless most people follow it. You couldn't have a standard if it was only followed by a minority. So in effect, he claims that most men are like most men in having short hair, and that most women are like most women in having either long or short hair or something in between. Definitely one of those. He continues:

"Whilst it is right that we should not continue with past discriminatory practices, it remains a fact of life that men and women have different physical attributes which, together with traditions and customs, mandate different conventional standards of appearance for men and women in a society. Like rules as to manners, these conventional standards of appearance are adhered to in order to maintain proper and decent presentation of oneself in the interaction with others in society."

The implication of this is that long-haired men are improper and indecent, but long-haired women are not. Remind us to cut our hair if we ever appear before these judges, because apparently, appearances speak louder than words. Whoever said that justice was blind? This statement rather begs the question of whether a fair and reasonable-minded person might think that the judges were biased against Long Hair because of his long hair when he appeared before them. How can they take him seriously when he does not maintain a "proper and decent presentation" of himself in his court appearances? Secondly, there is no "mandate" and no "mandatory" standard of appearance to which we must all adhere, other than the common law against acts outraging public decency, which long hair does not breach.

Whether the judges have short hair themselves, we would not know, because apart from the Chief Justice, they all wear shoulder-length wigs. Apparently these were once "essential wear for polite society" in the 1680s under Charles II.

Footnote

Incidentally, neither the CFI nor the Court of Appeal was asked the separate question of whether male prisoners should be entitled "upon request" to have their hair cut before "production in court", as women prisoners are in the Standing Order. Surely men are entitled to look smart (if not "proper and decent") when appearing in court too? This rule again reflects a biased view that a woman's appearance is more important than a man's.

© Webb-site.com, 2018

Organisations in this story

People in this story

- Au, Thomas Hing Cheung

- Cheung, Andrew Kui Nung

- Lam, Johnson Man Hon

- Leung, Kwok Hung (1956-03-27)

- Poon, Jeremy Shiu Chor

Topics in this story

Sign up for our free newsletter

Recommend Webb-site to a friend

Copyright & disclaimer, Privacy policy